One of my mentors, John C. Gardner, died on September 14, 1982. Here is a brief memory of studying with John.

"One of the dangers in teaching or taking creative writing classes lies--and here I'm speaking from my experience again--in the overencouragement of young writers. But I learned from Gardner to take that risk rather than err on the other side. He gave and kept giving, even when the vital signs fluctuated wildly, as they do when someone is young and learning. .." Raymond Carver

Listen to the footsteps that your words take inside the walk of a sentence. Each word on your tongue. Lips and tongue. The mechanics of the word inside your mouth. Writing does not cover the wound, heal the wound; writing is the wound, the making visible of the suture. A way to breathe. The act of writing is the need, the deep desire, to penetrate the bone. Recover broken bodies. A way to battle the invisible monsters chewing the blood of speech.

As my teacher, John C. Gardner did not so much bring me to the word, as he carried me home once again to the flesh of the words that so much of my academic background had year after bloody year destroyed. He returned the eye that the king of trolls had stolen from Woden, my eye that too many literary critics had forced to become blind to listening. John made reading–in place of mere meaning-scavenging–possible once again. The boundless page of schizophrenic resistance. He put me in a position to begin forgetting in order to remember, not with some sort of Garden of Eden innocence, but with voices, echoes, and uncertainty.

John blew off the institutional dust that had, because of the desire of the academic industries to explain away beauty, accumulated over William Faulkner’s breathing and returned me to the dizzy breathlessness of Faulkner’s writing. Faulkner’s words, John reminded me, are made from blood, are marked in blood; they are not simply palaces of meaning, convoluted places where dead or dying scholars meet to whisper over the runes in secretive hermeneutic struggles. Read Faulkner’s sentences aloud. Feel them move, not from the page, but from inside the depths of your own body. It was with the recovery of this listening eye that I was finally able to burst into writing.

John taught me to hear in physical ways the rhythm of my lips forming words. The touching of two lips, of lips to tongue, each-to-each. The ineluctable modality of the visible. Closed eyes on a beach.

They watch on, evil, incredibly stupid, enjoying my destruction.

'Poor Grendel's had an accident,' I whisper. 'So may you all.

--John Gardner, Grendel

In his novel Grendel, John has Beowulf teach this same lesson to a stunned, inarticulate monster. Here through this private battle between Beowulf and Grendel, John responds to the sick, immoral shapers of hollow words. Some of whom were his peers. For me, this final chapter of Grendel performs John’s philosophy of teaching more clearly than any other work that John had ever written or spoken.

Grendel is forced to move down into his own body, to return to the bonecave of his body-speech, to recognize the making of his own pain, and to sing pain, not to simply sing about pain, but to sing pain. To feel joy, to live inside the joy of coming to the meat of body. And Beowulf does not allow Grendel to merely howl, dumbstruck mumblings, but forces him to sing with syllables licking the cold-blooded world. Let out fire. Break into the wordhoard. Raving hymns. I always wanted John to read my work and, like Grendel, to respond to my language by saying, “Hooray for the hardness of walls!” Back then he never did say that of my work.

Through his exercises, through his responses to my writing (especially in those responses to my stories or characters when he felt I wasn’t being honest, when he felt that I was cheating my reader), through his mere physical presence, something about his being-in-the-world, John discovered ways to put me inside these flames of writing. There were times when I felt or, more accurately, feared that John cared more passionately about my characters than I did. That I just wanted to use my characters in order to tell a story or to make a point. These characters just happened to be in the neighborhood, hanging out in the corridors of my tiny mind waiting for their godotean author, so I could “use” them for my own perversions.

O the ultimate evil in the temporal world is deeper than any specific evil, such as hatred, or suffering, or death! The ultimate evil is that Time is perpetual perishing, and being actual involves elimination. The nature of evil may be epitomized, therefore, in two simple but horrible and holy propositions: 'Things fade' and 'Alternatives exclude.' Such is His mystery: that beauty requires contrast, and that discord is fundamental to the creation of new intensities of feeling. Ultimate wisdom, I have come to perceive, lies in the perception that the solemnity and grandeur of the universe rise through the slow process of unification in which the diversities of existence are utilized, and nothing, 'nothing' is lost. -- John Gardner, Grendel

Back then, I was filled with stories “about” ideas, filled with all sorts of Germanic philosophical idea(l)s and very little, if any, living. John relentlessly pounded that foolishness out of me until at last I gave up its ghost and returned to the childishness of writing inside a curiosity for the world. Actually, John’s “feeling” about my works was never simply a feeling; John’s intuitive readings were always more complicated, more significant than simple feelings. To this day, I know that, during those rainy Binghamton nights, John did care about my characters in ways that I did not quite yet understand and that he wanted, as much as anything else, for me to care as deeply about my characters as he did. He did want me to recognize why it was important for me to know the reason that one of my characters hesitated before crossing the street or why a character was so disturbed by a pebble in her shoe. Even if the “reason” was not intrinsic in any way to the plot, or if the “reason” was never even implied in the story, John knew that I had to know in my writer’s heart and mind why this particular character hesitated at this particular time in that particular place.

As a teacher of fiction writing now, I quite often find myself returning to John’s concerns with my students. I remember John once saying to me that this one character seemed really convenient to me, the writer, but how convenient or important was he to the story? Another time John simply and ever so briefly pointed to a sentence in one of my stories and said: “That must have been an easy sentence to write.” I was struck dumb, never so silent in all my life.

When I got back home to my tiny apartment in Endicott, I worked on that sentence. Worked it over and over. All weekend: me and my simple sentence. My easy sentence. The ringing phone went unanswered. Gary knocked on the door to my apartment and yelled in at me. Tempted me with chili and beer. I think the police came. (Maybe I’m inventing that part.) The Pirates were beating the Orioles in the Series, but I went on writing that sentence. Rubbing out words. Stealing words from my neighbors, from poets, and from misbegotten angels. I even dared to go so far as to be original and plug in some words of my own making. I called such words: inspiration. Words from the sacred fount. I forgot to eat for the entire weekend. Two or three times, I nearly committed suicide rewriting that sentence. I screamed out the window at the drones moving from the IBM plant to their cars. I told each and everyone of them that they knew nothing about time. That sentence almost killed me. I’m still at work on that damning sentence. I hope to have it finished soon.

In a world where nearly everything that passes for art is tinny and commercial and often, in addition, hollow and academic, I argue--by reason and by banging the table--for an old-fashioned view of what art is and does and what the fundamental business of critics ought therefore to be. Not that I want joy taken out of the arts; but even frothy entertainment is not harmed by a touch of moral responsibility, at least an evasion of too fashionable simplifications. --John C. Gardner, On Moral Fiction

The very first time that I encountered John on Binghamton’s campus was four days or so before the beginning of fall semester, 1979. He grabbed me by the elbow and pulled me down the hall with him into the men’s room. Our first official conference. I was more than a little tentative. “What are you working on?” “How is it giving you problems?” “What are you reading?”

There was never any beginning or ending of semesters with John; there was always and only writing. And John made it seem like there was nothing more important in God’s universe than my writing. He told us to forget our other classes and just write, only write. And rewrite. But he always wanted to know what we were reading. He told us to forget those other classes but only in the sense that we should be reading so much more than any other class could possibly have us reading. And writing. Don’t let anything get in the way of the writing.

I remember John’s hands wrapped around his pipe. His scent. I remember descending into the basement of the English Department building at S.U.N.Y.-Binghamton and thinking this is the home of John, Grendel’s dragon. Smoking. I can’t imagine John in a smokeless building. Knowing John, he’d burn such buildings to the ground. Return such an idea to some level of Dante’s Hell. Why should buildings be kept so innocent of a man’s presence? John’s steaming pipe was a part of his signature. I am thankful that I studied with him before the panics of second hand smoke. Of course, John was not much for obeying signs. And he belonged in that basement, or, more aptly, the basement belonged to John. He was “of” the basement. Soiled man of mud. The earth. Other professors seemed out of place down there. Almost frightened by the cold, damp, crusty hallway. All of them seemed to be struggling to get better offices, offices on the first floor among the living. Not John. This was John’s lair. He once told me that the walls of the school would fall down if he ever left.

Now, when I return to Binghamton, more than anything else I feel John’s absence. The halls no longer seem to be on fire.

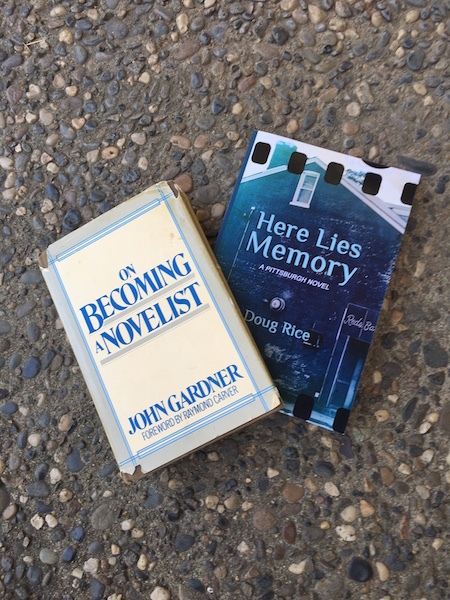

What the best fiction does is make powerful affirmations of familiar truths...the trivial fiction which times filters out is that which either makes wrong affirmations or else makes affirmations in a squeaky little voice. Powerful affirmation comes from strong intellect and strong emotions supported by adequate technique. --John C. Gardner, On Becoming a Novelist

_______________________________________________________________________________

To stay up to date with news about readings, gallery shows, publications, and special offers, sign up for the Doug Rice Newsletter.